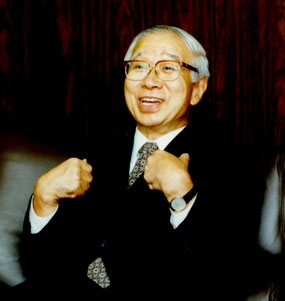

| Interview with Mr. Yasutaka Miyamoto, President and CEO of Shinkin Central Bank November 5, 2001 By Keith W. Rabin, President of KWR International, Inc. KR: Hello Mr. Miyamoto. Thank you for taking time to speak with us today. YM: It is my pleasure. I greatly appreciate this opportunity to speak with the readers of the KWR International Advisor. Before beginning, however, please allow me to first express my deepest condolences to anyone effected by the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington. This tragedy represents a great affront against all democratic and peace-loving peoples and I would like your readers to know the Japanese people share the pain and sadness that has been caused by this needless suffering and loss of life. We believe these terrorist acts were aimed not only at America, but at the entire global community. We wholeheartedly support U.S. efforts to fight the global terrorist menace. As a small token of SCB’s determination to help effected families and to alleviate some of the pain that has been afflicted, I recently instructed our New York office to make a $100,000 donation to New York City Mayor Rudolph Guiliani’s Twin Towers Fund. KR: Thank you Mr. Miyamoto. We sincerely appreciate this kind gesture as well as the spirit of your remarks. To begin, we’ve been hearing lots of negative news about Japan and Japanese banks for many years. What is the problem? YM: It is true the Japanese economy has not been doing well for some time now. Many people blame the banks. I wholeheartedly agree with those who emphasize the need to resolve the non-performing loan problem. Yet in my eyes the Japanese banking situation reflects troubles in the overall economy. Having spent most of my career in the Japanese Ministry of Finance, I witnessed the Japanese miracle from a unique vantage-point. Our progress was simply amazing. However, in retrospect it is clear our financial system did not keep pace with our extraordinary growth. We became a victim of our success and too comfortable and resistant to change. Moving forward, Japan needs to restore the dynamism it exhibited in the past. Equally important is the emphasis being placed on small and medium businesses -- which employ 70% of the Japanese workforce and constitute the bulk of our economy. These businesses have had a tough time over the past decade, but without a recovery in this sector there is little hope for Japan at large. Shinkin Central Bank (SCB) has a special interest in this sector as our member Shinkin Banks and shareholder base is composed solely of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME). Thankfully, SCB, which I head as President and CEO, stands as one of the strongest banks in Japan. We are now moving to draw on our strength to promote the competitiveness of our member banks and their shareholders. Utilizing a strong consolidated capital ratio of 16.52%, a sound asset structure that includes a risk management asset ratio of 0.92%, efficient management (per head $166 million, triple that of the major city banks), an expense ratio of 0.13% (1/8 of major city banks), and one of the highest ratings of all Japanese financial institutions (S&P long term counter party rating of AA- and A1 from Moody’s), we believe we are up to the challenge. This will allow us to support our member banks and through them to facilitate small and medium businesses activity in this vital sector. KR: Over the past decade Japan has begun to regain momentum several times, with minimal results. International investors therefore remain very skeptical. What can we expect from Japan moving forward? YM: Economic recovery in Japan is more important than ever before. Simply put, the global economy could support a weaker Japan when the U.S. and Europe were exhibiting strong productivity and growth. The terrorist attacks, however, have put increasing pressure on already weakening economies in the U.S. and other markets throughout the world. Like anything else, however, these complex problems will not be resolved in linear fashion. It is often said the Japanese people move very slowly until consensus is reached and we then move rapidly toward implementation. Significant momentum was achieved this year with the election of Prime Minister Koizumi. The actions of his government have further enhanced movement toward the public consensus needed to sustain the often painful reform process. While there will be ups and downs, I believe we are trending in the right direction and the process is now irreversible. In respect to the banks, the NPL problem must be resolved to restore our long-term competitiveness. This is stifling our progress and ability to move forward. For this reason the government has accorded the NPL issue the highest priority within its ongoing economic reform program. Measures will be implemented to strengthen the inspection of financial institutions. Until now, major banks were inspected every two years. Now, Japan’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) will conduct inspections every year. Follow-up reviews will also be held every six months. This will help to catch problems as they arise. Furthermore, when inspections reveal serious problems, banks will be required to have the borrower file for court protection, develop a voluntary restructuring plan or dispose of troubles loans to Japan’s Resolution Collection Corporation (RCC). The FSA will also take steps to check banks with loans to companies whose share prices and credit ratings have declined dramatically. Even more importantly, the RCC will play a more important role. It will intensify its procurements to resolve this problem by the end of FY 2002 for existing NPLs and for new NPLs the following year. Significantly, proposals are also being considered to allow the RCC to expand procurements beyond failed and effectively failed loans. This will further strengthen the balance sheets of Japanese financial institutions. The RCC will also use debt/equity swaps to write off bad debt. Shares obtained through these instruments will be placed into a fund established in cooperation with the Development Bank of Japan and private investors. Can you tell our readers more about SCB and member Shinkin Banks? YM: Shinkin Banks are cooperative regional financial institutions based on a membership system. They are not corporations. This gives them a distinct personality that is different from banks owned by stockholders. Shinkin bank members are SME's and individuals, all from within a prescribed geographical area. Anyone who lives, works, or has an office within a shinkin bank's area of operation can become a member. In the case of businesses, they should have no more than 300 employees or less than $7.5 million in capital. In principle, loans are made only to members, although lending to non-members is permitted under certain conditions. However,shinkin banks can accept deposits not only from members but also from non-members. At the end of March 2001, there were 371 shinkin banks in Japan, which had a total of 8,480 branches, 137,897 directors and employees, 8,940,984 members, total deposits of $865 billion and an outstanding loan portfolio of $551 billion. Shinkin banks control about 16% of total deposits and 11% of total loans in Japan’s financial system. This makes shinkin banks a significant part of Japan’s financial system. SCB has investments totaling$194 billion. This includes: $37.5 billion (19%) in short-term money markets, $97.8 billion (50%) in securities (i.e., primarily government and corporate bonds with only 0.3% invested in stocks), $53.7 billion (28%) in loans, and $4.3 billion (3%) in other investments. As the central bank for member Shinkin banks, SCB maintains a high liquidity of assets. Our ratio of investment securities to deposits is larger than that of loans to deposits, with an emphasis on treasury bills/notes and corporate bonds that enhance stability and which minimize the inherent volatility of more risky securities. The amount of stocks is $0.6 billion. It is 0.3% of the total investment portfolio, with $0.4 billion of this $0.6 billion of stocks is allocated to stocks of our subsidiaries. The ratio of stocks to capital is 8.2%. Significantly, unlike many other Japanese financial institutions, we have minimal cross-shareholdings. KR: You emphasize the financial strength of SCB, however, the data reveals that member Shinkins do not possess the same asset quality. Is this a case where transfer-price accounting has shifted bad loans and assets to your member banks to promote your own financial strength? YM: SCB provides loans to local companies when a shinkin bank cannnot provide them by itself. This includes loans to companies that have grown to such an extent that they are no longer eligible for loans from shinkin members. Therefore, let me emphasize that there are no conflicts between shinkin banks and SCB in respect to providing loans. As with many other Japanese financial institutions, it is true that many shinkin banks have had serious problems since the collapse of the "bubble economy" in Japan. Problems related to bad debt, however, have for the most part been due to overall weakness in the Japanese economy as opposed to imprudent lending. To some extent we attribute this to the fact that we are a cooperative institution. Therefore our members are more cognizant of risk and exposure within their local economies, as opposed to the major city banks that have a more centralized business model. Shinkin bank rules also restrict lending to individual members up to the limit given by the Shinkin Bank Law. This represents a ceiling on the percent of total capital that can be extended to a single entity to protect the financial integrity of a particular shinkin bank. Within our own operation, SCB needs to maintain as strong a credit rating as possible. This protects our ability to provide member shinkin banks with the liquidity needed to provide stability throughout the shinkin banking system. SME's represent 99% of all companies in Japan in terms of entities, as well as slightly less than 70% of all employees. It is therefore critical for shinkin banks to respond to the needs of these companies and for SCB to facilitate SME development in Japan, though our ability to provide, and access, capital at extremely competitive rates. Let me emphasize that this does not mean we coddle our members, nor do we seek to keep them operational in the sense of the "zombie" institutions that have been highlighted so often in the media. For example, in 1999, two shinkin banks — the Kyoto Miyako and Minami Kyoto Shinkin Banks - had grave problems related to bad real estate, construction and textile-related loans. Examinations by government regulators reinforced concerns over their potential failure. Our management acted quickly, recognizing if both banks failed there could be substantial damage to the local economy and the overall shinkin system. With the blessing of the government, who provided insurance support, the Kyoto Chuo Shinkin Bank assumed control of these two troubled shinkin banks in early 2001. This allowed a continuation of customer service without interruption. At the same time, SCB provided a subordinated loan of around $330 million to the Kyoto Chuo Shinkin. This helped to balance any potential losses that may have resulted from its need to absorb bad loans from these two institutions. Without our own strong asset base and credit standing, it is doubtful if this would have been possible. On the other hand, our ability to come to these decisions represents a significant evolution of our thinking and management style. Thirty years ago in 1971, we established the Shinkin Bank Mutual Assistance Fund System to maintain the credit standing and financial health of the shinkin banking industry. All member banks provide advance funds to the System, which provides assistance to financially troubled shinkin banks. Recognizing the need for change, the System’s charter was modified in 1996. Instead of providing assistance to individual institutions, it now focuses on helping troubled shinkin banks to merge with stronger partners. The government also initiated a deposit insurance program in the shinkin banking industry in fiscal 1999 to promote mergers and other measures to deal with failed banks. Since its establishment, the System has successfully handled 40 cases, including eight bankruptcies in fiscal 2000 alone. As a result, SCB is generally on target with respect to dealing with bankruptcy cases among its members. By handling these matters internally in a prompt and efficient manner, the System has raised the average credit standing of shinkin banks. KR: Can you tell us more about your management philosophy and plans for the future? YM: SCB strives for the growth of the shinkin banking industry and the overall development of the Japanese economy. We therefore serve as a financial institution that combines the roles of a central bank for member shinkin banks, a major institutional investor, and regional financial institution. Our bank will continue to fulfill these duties for our member shinkins and to work to maintain our sound management at the same time. This will enable us to meet our member’s fund operation needs, help them to broaden their business strategies, and to provide assistance to enhance their overall credibility. Within this context we will do our best to boost profitability and raise our capital ratio, to place our business on an even firmer footing. We understand that SCB's strength derives from the strength of our member shinkin banks. Therefore we are aggressively moving to strengthen the management capabilities of shinkin banks through the delivery of management advisory services. We have begun to form joint project teams with individual shinkin banks. They are charged with developing precise analyses of management issues from three perspectives–that of the shinkin banks themselves, their customers, and competitors. In addition to devising and recommending strategies in such areas such as marketing, profit and risk management, corporate structure and human resource management, we suggest processes and systems to enable practical implementation. We also provide follow-up services to support policies for the revitalization of the regions in which they operate. SCB has taken this first step to help develop a management diagnostic system for all shinkin banks. This system was applied to three shinkin banks over the last year. We are very pleased with the results. Additionally, in April 2001, to enhance our strength and institutionalize our ability to address emerging needs and problems, a System for Strengthening the Management of Shinkin Banks was established through a dialogue among member shinkin banks, the National Association of Shinkin Banks, and SCB. The new system is composed of three components, each managed by SCB. These include management analyses and consulting systems to provide necessary information from, and counsel to, member banks and a capital strengthening system to help address the capital needs of member banks. As the central institution representing Japan’s shinkin banking sector, we believe our own operating foundation will become stronger as a result of these initiatives. In the case of capital injections, SCB will inject up to 25% of the capital of the shinkin bank by purchasing preferred shares or by providing subordinated loans. To maintain the strength of SCB, we have established a limit for the total amount of financial support through vehicles such as subordinated loans, which will not amount to more than 15% of our capital. KR: You noted that Japan is only as strong as its SME sector. I imagine this is also true of SCB as well as the local shinkin banks themselves. Is there hope for these enterprises? What are SCB and its members doing to promote the recovery of SME’s as well as the regions in which they operate? YM: The profit environment for SME's is more severe than those of large companies. However, restructuring is often easier in smaller firms as decision-making power is usually centralized in the owners of these enterprises rather than the larger, more complex management and shareholding structures found in larger firms. Companies that reduce labor and operating costs -- helped along through the improved use of information technology -- will see their profitability improve steadily. This trend is already underway and is reflected in the ordinary profit of small and medium sized companies. Measured as a percentage of sales, SME's saw their profits bottom out in fiscal year 1998, and they have since risen to 2.6% in fiscal year 2000. This is a level last seen in the early 1990s. While we still have far to go, this is significant progress. In addition to helping our member shinkin banks to enhance the competitiveness of their clients, one of our strongest challenges is how to provide these firms with the funds they need to expand and finance their operations. This is problematic. According to a survey by Bank of Japan, financial institutions — especially those that are struggling with bad loans — have had to make their lending criteria stricter. Many small and medium sized companies note that their working capital needs remain severe, though the availability of these funds have declined drastically. Additionally, there has been a rapid movement in Japan away from the relationship-style banking practices that has governed our country during the post-war era in favor of western style credit analysis and practices. Companies, and in many cases our member banks themselves, lack a familiarity with these practices so we spend a lot of time working with our members to facilitate this essential transition. KR: Thank you very much Mr. Miyamoto for your valuable time. Before concluding are there any parting comments or conclusions you would like to leave with our readers? YM: Thank you Keith as well for this opportunity to speak with the readers of the KWR International Advisor. In addition to the points we have already addressed, I would like to close with a message of optimism. Financial and technical support for SME's is one of the most important issues facing our country, because the revival of these enterprises, which employ two thirds of the Japanese workforce is essential for Japan’s economic recovery. SCB is determined to draw upon its strong capital base and management expertise and capabilities to help leverage this transformation. We invite your readers to travel to Japan to explore the many trade and investment opportunities that are arising as a result of these developments. If we can be of help in any way, we ask that they contact our offices in Japan, New York, Hong Kong, Singapore and London so that we might be of assistance. The preceeding information is provided by: KWR International, Inc. New York, NY 10023 Phone: +1.212.532.3005 Fax: +1.212.799.0517 E-mail: kwrintl@kwrintl.com Website content © 2001 KWR International |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recent

moves by our government are a definite step in the right direction.

Similarly the bankruptcy of Mycal and other firms show that

Japan is not conducting business as usual. These events would

have been unthinkable only a few years ago.

Recent

moves by our government are a definite step in the right direction.

Similarly the bankruptcy of Mycal and other firms show that

Japan is not conducting business as usual. These events would

have been unthinkable only a few years ago.

As

shinkin banks and SCB are cooperative financial institutions,

only members can invest in common shares. That said, however,

to enhance our financial strength and to offer outsiders an

ability to invest in our future, we elected to issue a private

offering of preferred shares worth $167 million in each of

the fiscal years 1995, 1996, and 1997, and $333 million in

fiscal 1998. In fiscal year 2000, SCB's preferred shares were

listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, in a public offering worth

$763 million. As a result, at the end of March 2001, the bank’s

capital ratio (BIS standards) stood at 16.52% on a consolidated,

or 16.28% on a non-consolidated basis. This substantially

exceeds the 8% minimum standard established by the Bank for

International Settlements. SCB will continue to increase its

net worth by accumulating internal reserves, and to use this

net worth, to increase its earnings.

As

shinkin banks and SCB are cooperative financial institutions,

only members can invest in common shares. That said, however,

to enhance our financial strength and to offer outsiders an

ability to invest in our future, we elected to issue a private

offering of preferred shares worth $167 million in each of

the fiscal years 1995, 1996, and 1997, and $333 million in

fiscal 1998. In fiscal year 2000, SCB's preferred shares were

listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, in a public offering worth

$763 million. As a result, at the end of March 2001, the bank’s

capital ratio (BIS standards) stood at 16.52% on a consolidated,

or 16.28% on a non-consolidated basis. This substantially

exceeds the 8% minimum standard established by the Bank for

International Settlements. SCB will continue to increase its

net worth by accumulating internal reserves, and to use this

net worth, to increase its earnings.

How

will we generate increased profits? Presently, our primary

source of profit is the interest income we derive from securities

investment and loans, including agency loans through member

shinkin banks. While retaining a commitment to maintaining

a strong, stable asset portfolio, we will seek to enhance

our profitability and competitive strength moving forward.

This will be achieved though improving our investment ability

(i.e., higher investment returns through corporate bonds and

global diversification); new loans, (i.e., to local governments,

corporations, non-residents, etc.); and fee-based businesses

(i.e., foreign exchange, settlement business, and new businesses

including Venture, M&A, and 401k etc.).

How

will we generate increased profits? Presently, our primary

source of profit is the interest income we derive from securities

investment and loans, including agency loans through member

shinkin banks. While retaining a commitment to maintaining

a strong, stable asset portfolio, we will seek to enhance

our profitability and competitive strength moving forward.

This will be achieved though improving our investment ability

(i.e., higher investment returns through corporate bonds and

global diversification); new loans, (i.e., to local governments,

corporations, non-residents, etc.); and fee-based businesses

(i.e., foreign exchange, settlement business, and new businesses

including Venture, M&A, and 401k etc.). Until

recently, many in Japan were blinded by our extraordinary

economic achievements and believed that our problems would

be resolved through a change in the business cycle. That is

no longer the case. We are now clearly aware of the need for

fundamental change. The strong support enjoyed by our newly

elected reform-oriented Prime Minister is strong evidence

of this fact. While one can argue over the pace of our actions,

the momentum is moving definitively in the right direction

and I believe the trend is now irreversible.

Until

recently, many in Japan were blinded by our extraordinary

economic achievements and believed that our problems would

be resolved through a change in the business cycle. That is

no longer the case. We are now clearly aware of the need for

fundamental change. The strong support enjoyed by our newly

elected reform-oriented Prime Minister is strong evidence

of this fact. While one can argue over the pace of our actions,

the momentum is moving definitively in the right direction

and I believe the trend is now irreversible.